This tribute by Judith White, author of Culture Heist: Art versus Money which exposes managerialism and foreshadows corporatisation at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (read review here), explores landscape in the paint of Sidney Nolan and the pen of Randolph Stow, and in the excited reverie of their imaginative minds.

Rimbaud, Stow, Rimbaud.

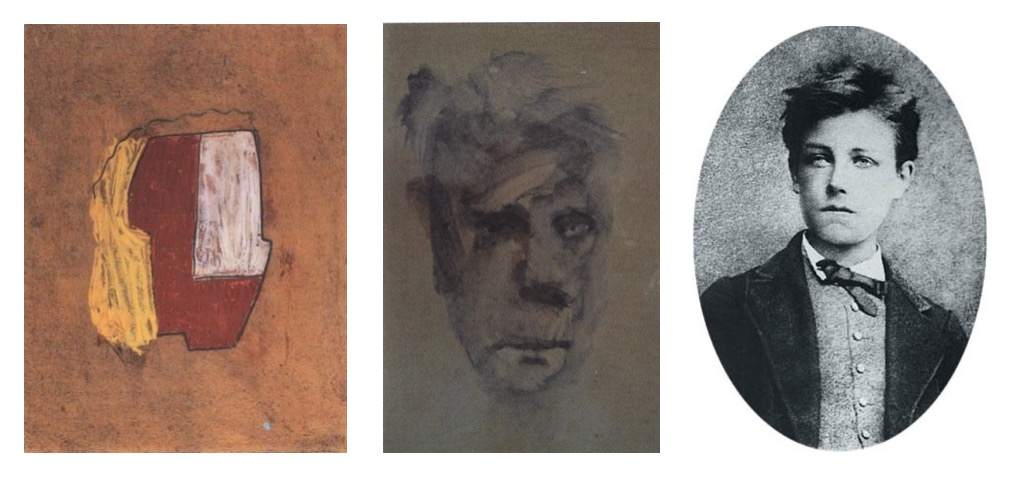

From left to right: (1) Sidney Nolan, “Head of Rimbaud”, 1938-39, collection Heide Museum of Modern Art; (2) Sidney Nolan, “Stow as Rimbaud as Stow”, 1963, collection University of Western Australia; (3) Arthur Rimbaud, photo by Etienne Carjat, Paris, October 1871

Outsiders both and friends for decades, Mick and Sid were contributors to the 1965 Yeats centenary book In Excited Reverie on which these Nolan Centenary tributes Imagining in Excited Reverie are modelled.

A TRIBUTE BY JUDITH WHITE

Mick and Sid: Explorers of the Australian landscape

“The poet makes himself a seer by a long, prodigious, and rational disordering of all the senses…

“… let us demand new things from the poets – ideas and forms.”

Rimbaud, Lettre du Voyant, 1871

To Barry Pearce, curator of the 2007 Sidney Nolan retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the key to understanding the artist’s journey lies in his reading of the 19th century genius of French poetry, Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud was “the model of the bad boy. He was dangerous, incandescent. He turned the whole poetic tradition upside down.” For Nolan, this was “a model of how he could break away from the suffocating life he thought he had”.1

The poet and novelist Randolph (“Mick”) Stow also drew inspiration from Rimbaud, whose intense outpouring of creativity stopped abruptly when he was just 20. Stow admired that, believing that “you should say what you had to say, then shut up”2 – something the writer himself would do several times, with long silences between his published works.

Nolan and Stow were groundbreaking modernists, each in his own sphere. Gallery director and art historian Patrick McCaughey believes Nolan “changed the nature of Australian art” and that he “discovered the power of the figure in the landscape as a means of giving the familiar Australian environment meaning and purpose, a resource of emotional feeling”.3

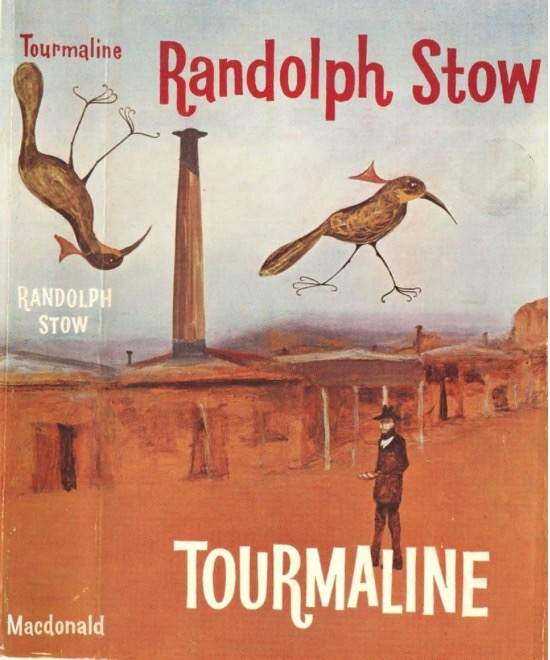

When I first read Stow’s masterpiece Tourmaline almost 30 years ago, it was one of those moments of illumination akin to looking for the first time at a great painting. From the opening page it was enthralling, depicting “no stretch of land on earth more ancient than this”, in which “we are tenants; tenants of shanties rented from the wind, tenants of the sunstruck miles”.

Stow had been drawn to the paintings of the modernists as a student at the University of Western Australia. Later, on one of the rare occasions when he was persuaded to put pen to paper about the creative process, he wrote about their art and his in terms of the inner and outer, terms that echoed Rimbaud: “The feeling, the sense, what a Spaniard would call the sentimiento of Australia: the external forms filtered back through the conscious and unconscious mind; that is what these artists convey… In that sense, the world out there is raw material. But only part of it – all the rest is mind. So – one is obliged to introspect… what I see in the end in Australia … is an enormous symbol: a symbol for the whole earth, at all times, both before and during the history of man… In its skeletal passivity it will haunt and it will endure.”4

A few years earlier Nolan had said in a London interview: “I was fascinated by the objectivity of the arid endless land. The land stated its terms and left you to your own adjustment… The distances, colour, and light of the centre are a challenge to any artist, and the rules of European painting don’t seem to apply out there. When I started to paint, I felt I was striving for something completely new. Now I feel this is presumption on my part… It is a continent as old as Genesis.”5

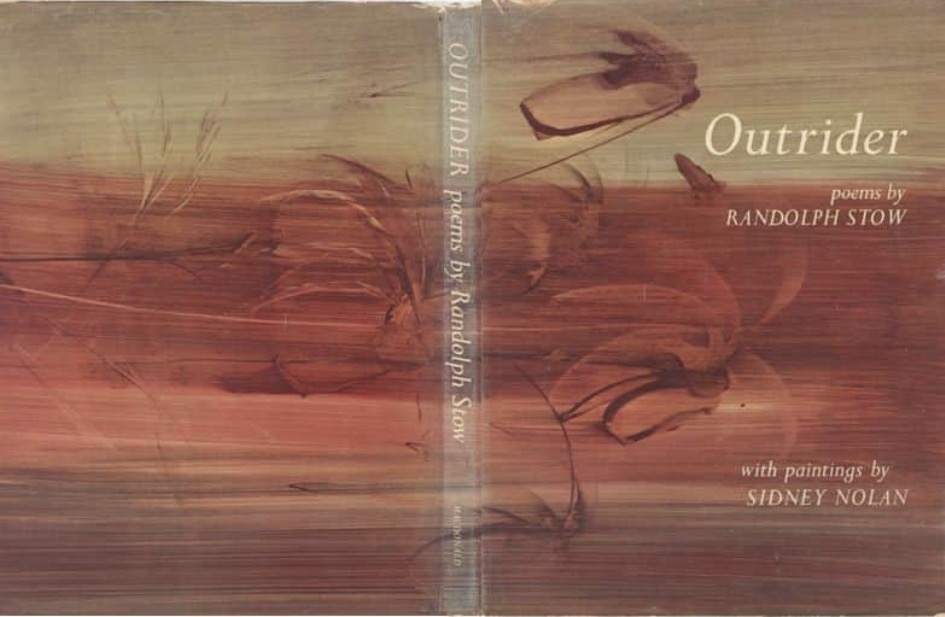

In 1961 Geoffrey Dutton, then editor of the journal Australian Letters, had the inspired idea of bringing Nolan and Stow together for his series of booklets by Australian artists and poets. The 24 poems to be published in the volume Outrider would be illustrated by Nolan. The collaborators were now both in England where Nolan, 18 years the senior, was living in south London with his wife Cynthia and her daughter Jinx. He invited Stow to dinner at their riverside home in Putney to discuss the project, and a decades-long friendship was formed.

Their artistic kinship was never better expressed than in ‘The Land’s Meaning’, the poem Stow wrote for Nolan and included in the collection. It is reproduced by David Rainey elsewhere on this website. It tells through the simplest outback imagery, tin-shed bars, flyspray, camels and all, of the exploration of the soul and the grief-stricken searching of a man “bushed for forty years”, and ends with the lines:

And I came to a bloke all alone like a kurrajong tree,

And I said to him: ‘Mate – I don’t need to know your name –

let me camp in your shade, let me sleep, till the sun goes down’.

Nolan produced seven plates and a wrap-around dust jacket (seen above) for the book. By this time he was already an established artist, internationally acclaimed and exhibited. Stow, at 26, had published his first three novels A Haunted Land, The Bystander and Penguin Australia’s first paperback title To the Islands, all set in his native Western Australia, as well as a volume of poetry, Act One. But he was still recovering from the traumatic events of 1959 in New Guinea, where he attempted suicide. In addition, despite the success of his early work, he was struggling financially. For a time, in these circumstances, Nolan was perhaps his kurrajong tree. Cynthia, of whom he became very fond, often fed him, and gave him days of work in their garden when he had no other income.

Outrider remains a landmark publication in the annals of Australian poetry. Dutton’s notes on the sleeve perhaps say it best: “A new and moving chapter [is] added to the Australian myth by the conjunction of two outstanding talents. In Sidney Nolan Australia has found a romantic painter to do for her what Turner once did for the sea, to capture her essence while progressively discarding the detail of her hitherto-dominant local colour. From his pictures simplicity, loneliness, terror, nostalgia and cruelty emanate through sand, rock and tree to re-create a land where only the strongest survives but from which no one altogether escapes. Randolph Stow’s poems are informed with the same understanding. Whether they deal directly with the Australian scene, or with other peoples and places, they are the outcome of an experience of exile which goes deeper than exile from country.”

Exiles they both remained, prophets more honoured outside their native country than in it. The Outrider poems were more enthusiastically reviewed in the British press than in the Australian media. Colour proofs of the book were the last gift the poet Ted Hughes gave to Sylvia Plath before her death.6 Back in Perth Sid rather stole the show. When the images were included in an exhibition of his work timed to coincide with the 1962 Empire and Commonwealth Games, the Duke of Edinburgh came to view them and quickly acquired the illustration for the poem Strange Fruit, giving a boost to Nolan’s prices.7

The writer’s original title for Outrider had been Outsider, but Stow had changed it on finding it had been used for another poet’s earlier collection. Outrider worked; the refrain of the poem of the same name reads:

My mare turns back her ears

and hears the land she leaves

as grievous music.

But the term “outsider” still applies to both the poet and the artist. Nolan told Michael Hayward in an interview the year before his death: “As a worker, as a son of a worker, going to a factory at age 14, I was fully conscious of being an outsider, because that’s what you are.”8

For Stow, being an outsider was probably more to do with his sexuality, about which he remained intensely private all his life. It seems it was harder for a son of the Geraldton squattocracy to come out in the 20th century than it was for Rimbaud, a son of the French bourgeoisie, in the 19th.

In any event their art made both Nolan and Stow outsiders in their own country. From 1950 until his death in 1992 Nolan never lived in Australia, although he continued to visit and for much of that time he continued to paint the country. Stow moved to England in 1960, and despite several attempts at returning could never settle back in his native land. The relative anonymity, diversity and tolerance of English life was an attraction, and both had also experienced the cultural claustrophobia of the Menzies years.

At the Art Gallery of New South Wales director Hal Missingham’s 1949 acquisition of Nolan’s Pretty Polly Mine and Carron Plains had been so shocking to the trustees that they temporarily banned him from adding further to the collection.

When Tourmaline appeared in 1963, with a brilliantly evocative dust jacket (seen above) by Nolan, Mick Stow became the target in Australia of the arch-conservative professor of English (later Dame) Leonie Kramer who called it “the reductio ad absurdum of the symbolist novel”. It was the start of an ongoing literary stoush, with Australian National University professor A.D. Hope, a Kramer supporter, writing in 1974 that Stow’s novels “continue to baffle competent and intelligent critics”.9 In these years, when the writer thought of returning to Australia to live, Nolan advised him against.

Their friendship endured. In 1963 the artist gave Stow a sketch, Stow as Rimbaud as Stow, drawing on the likeness between his young friend and the French poet – a lasting tribute to their shared outlook.

Nolan also recommended the writer for a Harkness Fellowship which enabled him in 1964-5 to work and travel in the United States, where he lectured on Australian art and literature. In 1969, when Stow returned to live in a Suffolk cottage close to his ancestral home, the Nolans came visiting.

After Cynthia Nolan’s suicide in 1976 Stow saw rather less of the artist, but unlike Patrick White who rushed to judgement about other people’s marriages, he was warmly supportive of Sid’s remarriage to Mary Boyd, which he thought “the best thing that could have happened to him”.

Kay Lanceley, wife of the artist Colin Lanceley, met Stow at a London dinner party in the 1960s with Lawrence Daws and found him “charming, funny, delightful” – much as she found Nolan. But as the years passed, Nolan was more in the world, while Stow retreated. Nolan had dark moments – his break with Sunday Reed, the death of Cynthia – but in general he was prolific, sociable and comfortably off.

Stow, though he maintained long friendships, was none of these. He relentlessly pursued Rimbaud’s path of “rational disordering of the senses”, at times drinking heavily, often burdened with ill health, both mental and physical, and frequently in financial difficulties. The poems and novels, when they came, were brilliant, but there were long periods of writer’s block and extreme introspection. Visitants, the novel that dealt at last with his New Guinea trauma of 20 years before, appeared only in 1979, shortly after The Girl Green as Elderflower, an exploration of medieval legend he had worked on during the healing time he spent in Suffolk.

Stow detested the literary circuit. He made an appearance at the Adelaide Writers’ Week in 1974 but while the Whitlam-era atmosphere and the exuberance of Don Dunstan’s South Australia were congenial to him, he disliked speaking about his work in public and shunned later invitations, believing that a writer’s work should speak for itself. He preferred the company of working people to that of the literati; he was at home talking to stockmen and Aborigines, farmers and seamen and pub-goers.

His affinity with Nolan was not through the public life of the art world but through their work, and in that they were close. Patrick White, Australia’s only Nobel laureate for literature and an early supporter of Stow, is generally regarded as the country’s pre-eminent writer in the 20th century. He will always remain a towering figure of Australian letters. But for the directness of his language, for his depictions of characters and of landscape, for the depth of his humanity, and for his resonance with the images of Nolan and the moderns, I derive greater pleasure from reading Stow.

I never met Nolan, but I met Mick Stow once, in the port town of Harwich, where he had moved in 1981, finally accepting the permanence of exile. In a fisherman’s cottage, with the Stour Orwell estuary at the end of the street, he made the home he would live in until his death in 2010. In the early 1990s I was in London, filing occasional features for press back in Sydney. The writer Peter Skrzynecki, a friend of Stow’s since the 1970s, had generously given me some of the books over a period of years, and now advised me about the best way to request an interview. I was to write a letter, mentioning Skrzynecki’s name, and if there was a reply I could then phone to make an appointment. I still have the card that came back from Harwich. Dated 10 November 1993, and penned in characteristic backward-sloping handwriting, it reads in part: “It is kind of you to want to interview me, but I’m afraid I’ve been interviewed to exhaustion and have nothing more to say on any subject. Of course I’d be happy to meet you, if you understand in advance that I’ve lived alone for a quarter of a century and don’t talk much.” He signed formally “Randolph Stow”.

We made an appointment. On a crisp, bright winter’s morning I alighted in Harwich from the Liverpool Street train, clutching in one hand a bottle of Margaret River wine, for Australia, and a jar of pickled onions, for rural England. I looked for the writer who was to meet me. The only people I could see, at the far end of the platform, were two men who looked like railway workers in jeans, donkey jackets and caps. As I approached one of them greeted me amicably; it was Stow. He carried a bag of chopped-up greens and vegetables and their purpose soon became clear when we walked down to the wharf. Four or five swans swam up and he began, tenderly, to feed them their lunch. A local wildlife expert had recently discovered that the birds were suffering from malnutrition as a result of being fed bread, and Mick had taken it upon himself to improve their diet.

Next stop was the pub, where the regulars greeted him warmly – “Mornin’, Michael!” – and glanced our way benevolently as we consumed pints of bitter and pies. Then came a walk up to the lighthouse which features in his last novel, The Suburbs of Hell. He was right – he didn’t talk a lot, but it was a companionable hour and he named for me every species of bird and every kind of tree we encountered, before heading for the warmth of the cottage at 28 King’s Head Street.

The house was small, tidy and frugal, one room on each of the three floors. A clock ticked peacefully and the cat Billie curled up before the fire. There was an atmosphere of writerly contemplation, of a life lived intensely, in solitude but with a certain depth of satisfaction. And there were small Nolans on the wall – one of a dog by a campfire, evocative somehow of Stow’s novel The Merry-Go-Round in the Sea.

Over a cup of tea Stow showed me documents he was still working on, to do with the Abrolhos Islands and the Batavia, the 17th century shipwreck off the coast of Western Australia and the subsequent massacre among the survivors. More resonance with Nolan: the artist had his own fascination with a fatal shipwreck – in his case the 1875 wreck of the Deutschland commemorated in Gerard Manley Hopkins’s most famous poem. For Stow, the Batavia had been a lifelong interest, and it seemed a likely subject for his next book, but in the end the work was never completed.

He walked me to the station as it grew dark, and I was sorry to say goodbye. We kept in touch for a while, but a year later, when I was due to return to Australia, he told me that his attention was now entirely taken up with the care of a young married man, a friend and neighbour, who was very sick with a terminal disease. This was Paul Gwinnell, who in the event would survive his friend by weeks.

After that I heard no more. When I learned of his death seven years ago, I thought of him going out in true Rimbaud style, having said his all. Jinx Nolan, recalling the days in Putney when he would come to lunch and walk along the towpath with them, wrote in tribute: “I thought Mick would always be alive. An extraordinary man, modest, dry wit and quietly brilliant … Tourmaline resonates in me.”10

In me too. Recently I went back to re-read all his books, one by one, in the order in which they were written, and found new meaning in each one.

I thought often of that day in Harwich, with a feeling that here at last, late in his tumultuous life, Randolph Stow had found a kind of peace. On the other side of the world from where he began, he had made landfall.

“Landfall” is the name of the last poem in Outrider:

And indeed I shall anchor, one day – some summer morning

of sunflowers and bougainvillea and arid wind –

and smoking a black cigar, one hand on the mast,

turn, and unlade my eyes of all their cargo;

and the parrot will speed from my shoulder, and white yachts glide

welcoming out from the shore on the turquoise tide.

And when they ask me where I have been, I shall say

I do not remember.

And when they ask me what I have seen, I shall say

I remember nothing.

And if they should ever tempt me to speak again,

I shall smile, and refrain.

CONTRIBUTOR

Arts writer JUDITH WHITE is a former executive director of the Art Gallery Society of NSW and the author of two books: Culture Heist: Art versus Money Brandl & Schlesinger 2017, and Art Lovers: The Story of the Art Gallery Society of New South Wales 1953-2013 AGSNSW 2013.

END NOTES

- Barry Pearce interviewed by Steve Meacham, The Sydney Morning Herald 20 October 2007.

- Patrick Maxwell email to Suzanne Falkiner, quoted in her biography Mick: A life of Randolph Stow UWA Publishing 2016, p388.

- Strange Country: Why Australian Painting Matters The Miegunyah Press 2014, p163, p171.

- ‘Raw Material’ Westerly 1961, reproduced in Randolph Stow: Visitants, episodes from other novels, poems, stories, interviews, and essays ed Anthony J. Hassall, University of Queensland Press 1990, pp407-8.

- Nolan on Nolan ed Nancy Underhill, Viking 2007, p295.

- Falkiner op cit p415.

- Sidney Nolan: Such is Life by Brian Adams, Hutchinson of Australia 1987, p162.

- http://www.acomment.com.au/2013/12/sidney-nolan-interviewed-by-michael-heyward-london-5-april-1991/

- “Randolph Stow and the Way of Heaven”, Hemisphere vol 18, 1974.

- http://austlit.typepad.com/cfn/2010/06/randolph-stow-19352010.html

Recent Comments