A TRIBUTE BY BRIAN ADAMS

Last year I published “Sidney Nolan’s Odyssey – a Life” timed strategically to mark the centenary of the painter’s birth in Melbourne on 22 April 1917. I assumed, quite reasonably, that several major happenings would be announced – particularly in his home town – to celebrate one of Australia’s most famous and honoured sons, culturally or otherwise. But apparently not!

There was a two-week, not-for-purchase exhibition of his earlier works from private collections by a leading art auction house in Sydney which was mainly a social event masquerading as a fundraiser for Opera Australia. This had only a peripheral, and as it happens, rather bizarre connection with the company for which Sidney designed only one production: a searing Il trovatore I produced as a simulcast on ABC Television in 1983 and which could have been curtains for the artist and his career because during rehearsals, while negotiating a temporary ramp between stage and auditorium, he lost balance and plummeted to the orchestra pit below in a moment of high drama to match anything in Verdi’s dark masterpiece. The result was three broken ribs and immediate hospitalization from which Sidney survived but had to miss opening night. Otherwise, there would have been far less to celebrate this year.

Presumably, that pay-to-view art show of Sotheby’s, which closed twelve days before Nolan’s centenary birth date, was never intended to be a philanthropic gesture, but organized with an eye to managing future sales of his work during a year when attention would be concentrated on Australia’s most expensive artist by auction records.

Their great rival Christie’s, however, has made no bones about cashing-in on the event by aiming high to attract his works for a major London auction later in the year reflecting ‘great themes, from early Kellys and including the Gallipoli paintings, Burke and Wills series, Mrs Fraser, Drought, Africa and Antarctica’.

Christie’s auction is timed to coincide with an exhibition of Nolan’s “Back of Beyond” drawings at the British Museum from the outback journey he made in June 1952 to record the effects of a drought that devastated the beef industry of Queensland and the Northern Territory. The trip resulted in a series of bleak sketches, a number of revealing photographs, and was followed by a series of paintings, some depicting a lunar landscape littered with animal carcasses mummified in grotesque death throes. They remain a testament to the awesome fragility of a continent for all forms of life, and in spite of their grim subject matter have come to rate among the artist’s greatest works.

Perusing my curiosity about how the centenary would be observed for a person I knew and admired both professionally and socially for 35 years, travelling with him extensively to make international television documentaries and writing two biographical studies, I paid a visit to the Art Gallery of New South Wales during February this year. I wanted to see what had changed since I was last there a couple of years before, and walking into the main entrance gallery, I found it looking brighter and more impressive than I remembered from many days filming there in the past with Christo, Gilbert and George, Robert Hughes and Sidney himself. I asked about plans for Nolan’s centenary at the information desk.

Staffed by three smartly dressed staff wearing the sort of uniforms seen behind the reception desks of upmarket hotels, I asked a young woman what special events were being planned by the gallery for Sidney Nolan. She lost her smile of greeting, looked blank for a moment and then asked, “Would you spell that name please.” Taken aback, assuming my speech had a certain clarity from being a former broadcaster and news presenter in New Zealand, Australia and at the BBC before my career changed direction, I carefully intoned “S-I-D-N-E-Y’ (pause) “N-O-L-A-N” as if teaching a small child to learn an unfamiliar name. She tapped each letter into her computer while I waited bemused, recalling this was exactly the spot where the artist in question, was ‘discovered’ by none other than Sir Kenneth Clark from London, having escaped the formative clutches of his mentors Sunday and John Reed’s Bloomsbury of the Bush at Heidelberg, Victoria. Although settled in Sydney by this time, he could never have imagined that his career was set in only one direction: London.

Revered in the art world for his energetic and scholarly directorship of London’s National Gallery, Kenneth Clark’s book “Landscape into Art” was an international best-seller and he currently held the prestigious academic post of Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford. His trip to Australia by sea in 1949 was to lecture on Cézanne and talk business with the National Gallery of Victoria as consultant for its well-endowed Felton Bequest. A man known to voice strong opinions, he was reported to remark, ‘Australia had the worst art, but the best Victorian pornography in the world’, referring to the bevies of naked young ladies disporting themselves across the canvases of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood eagerly bought by Australian benefactors to challenge the rigid moral codes of a previous century

Visiting Sydney’s State art gallery, Clark was proudly shown their collection of the so-called Heidelberg School of plein-air painters, finding them small and unadventurous when compared to the French Impressionists, and was about to leave when he noticed a painting entered in the annual Wynne Competition for landscape that attracted his keen eye like a beacon for its ‘remarkable originality and painter-like qualities’. The director Hal Missingham was unfamiliar with the artist and dismissed him – or her – as ‘a nobody’ but Clark insisted on seeing the exhibition catalogue where he found the painter’s name and the picture’s title: “Abandoned Mine” from his recent exhibition of “Queensland Outback” subjects.

Given an address at Wahroonga in the northern suburbs of Sydney, an appointment was made by telephone for the distinguished visitor to visit Mr Sidney Nolan’s studio that afternoon. The viewing took place in sweltering heat with the almost deafening sound of cicadas in the trees outside, and the artist dressed in his painting attire of khaki shorts. A frosty atmosphere was generated by his wife Cynthia who resented the intrusion which interfered with her habitual afternoon nap. Ignoring this, Clark was delighted with what he saw and bought “Little Dog Mine” painted on hardboard with Ripolin enamel from the same series he’d seen earlier in the city. On leaving, he offered to assist the artist with contacts should he be planning to visit England and then departed with his companion in their waiting taxi, ‘confident that I had stumbled on a genius’.

Nolan remembered that visit to his studio as a day of reckoning: “Like the mountain coming to Mahomet, though I was completely thrown by Clark’s oblique remark about going to England. On first sight I thought that he and his Burke (Joseph Burke, recently appointed to the Herald Chair of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne]) were a bit of a Pommy joke, what with their jolly-good jargon that made our supposed common language sound like some foreign tongue, wearing their tailor-made suits on a stinking hot day and flaunting exquisite gentlemanly manners.” But the scholarly Clark stirred something in the artist while studying his work in the afternoon heat with an air of supreme authority. “I’d never experienced anything like that before, certainly not in Melbourne or at Heide. So in spite of all the overt Englishness he displayed, I knew I must go to England, in spite of my wife’s refusal point-blank to even consider it because she had done her own grand touring years before and insisted on settling down to a quiet life in Sydney.”

My recollection of that pivotal point in Nolan’s early career which, had it not been for Clark and Burke’s unexpected visit, would almost certainly have turned out differently, was interrupted by the gallery receptionist telling me that she could find no special events scheduled for Sidney Nolan. Attempting to be helpful, she suggested I walk around the corner to where some of his paintings, including the single most expensive Australian artwork sold at auction ($A5.4 million), were hung, together with some of his contemporaries like Sir William Dobell. I thanked her as gracefully as possible in the circumstances and departed, not needing to see pictures I was thoroughly familiar with, having made television documentaries as well as researching and writing biographies of both the artists mentioned: “Sidney Nolan – Such is Life” and “William Dobell – Portrait of an Artist.” I could only assume that other State galleries and the National in Canberra were content to observe this centenary by drawing on their own collections and leaving it at that.

An exception was the Heide Museum of Modern Art in Victoria where Nolan painted most of his famous Ned Kelly series during 1946-7 (but not “First-class marksman” displayed in Sydney) on the kitchen table at the Reed’s Heide farmhouse, which would make him at the age of thirty a premature old master in his own country. His Man in the Iron Mask, an iconic Kelly image perhaps derived in the painter’s mind as much from Alexandre Dumas as the notorious bushranger’s own ferrous armour, would dominate the rest of his creative life and reputation. Full marks then, to the excellent Heide Museum for arranging a programme of Kelly-focused talks and tours throughout 2017.

The rather sparse centenary celebration in Australia for someone of such standing in its culture can be accounted for. I experienced anti-Nolan sentiments when writing and directing the 1987 television documentary Sidney Nolan – Such is Life planned as a personal retrospective of his brilliant career filmed around the world to mark his 70th birthday. An expensive production, it was financed by RM Productions of Munich, the Irish national broadcaster RTE and Britain’s Channel 4, but needed a partner willing to underwrite the obligatory Australian sequences. I’d explored similar territory a decade previously in my 1977 film Nolan at Sixty, written and narrated by Kenneth Clark – Lord Clark of Civilization as Robert Hughes dubbed him – and co-produced by the ABC and BBC on a big budget for international distribution. But sentiment regarding the artist had turned sour during that decade, with no Australian broadcaster wanted to participate in the Such is Life film, a rejection expressed bluntly by an ABC executive: “We’ve shown more than enough of Sid Nolan, thank you very much!”

As far as I know, that documentary has never been shown on television domestically, although Peter Neustadt’s plucky CEL company, marketing video cassettes of Joan Sutherland’s Australian Opera performances that I produced as ABC simulcasts, provided the necessary local funding to allow it being made. Thirty years later, with home entertainment technology having progressed at a breakneck pace from the video Stone Age, copies of the Such is Life video cassette issued by CEL Arts are in demand this centenary year – if you can lay your hands on one.

The impression that Sidney Nolan had sold out of Australia by basing himself overseas gained ground as early as 1961 when a mixed show at London’s Whitechapel Gallery “Recent Australian Painting” included a “Leda and the Swan” subject and the first major Gallipoli picture to be seen in public. The young and audacious Brett Whiteley was represented by a group of fleshy abstract landscapes which Nolan admired. But at the opening, Brett, aged 22 and most probably stoned, started to make snide remarks about ‘Sid’s international successes’, which made Sidney feel that he had been fooling himself to imagine that with his London success he was somehow carrying the flag for Australian art. Another young painter from Australia rather drunkenly pointed out that all Sid had done during his time away from home was to muddy the waters, blocking the public’s acceptance of those artists who had not compromised their integrity, or identity, by living overseas. Instead of carrying the flag, Nolan was accused of trying to steal it.

He reacted: “I got a terrible shock, being made to feel by Brett and the others that all I had been doing was to hold up the game and stop real artists, like them, from coming through.” He claimed to lose his Australian innocence as a result of the Whitechapel show and retreated from believing it was honourable to think of himself as a cultural ambassador for Australia, telling Arthur Boyd, his closest friend: “They act like barbarians and the honeymoon is over for me. I say with all honesty, Arthur that I can no longer admit with hand on my heart that Australian civilization deserves ipso facto to flourish, as I’d thought up to now.”

Following a lengthy absence from what Sidney called ‘the English art game’, while they travelled in Europe and America, the Nolans had returned to London in 1960, bought a house and settled down to become increasingly prominent in the capital’s cultural scene. Nolan was approached by the social observer and editor of fashionable Queen magazine Mark Boxer, to contribute a series of articles because, looking ahead, he backed Sidney Nolan and Francis Bacon as likely to be the dominant painters in Britain through the Sixties.

Cynthia was suspicious of this approach, having heard her husband criticized by his painter friend from Heide days, Albert Tucker, for repetitive imagery in the controversial but commercially successful London exhibition “Leda and the Swan”. “I’d known Albert for a long time,” he explained, “and that comment caused a very destructive situation, especially when he accused me of stealing a march on him by licking Kenneth Clark’s arse.”

Clark, Boxer, and Bryan Robertson, the influential curator and art manager, gained immense publicity for Nolan at this time, and according to the artist: “Lilian Somerville of the British Council tried to get me to drop my Australianisms, change passports and integrate more into the English scene to get a show at the Venice Biennale, warning that my association with Kenneth Clark was the kiss of death.”

Staunchly retaining his original travel document, the unlikely bond between the two men developed into a firm friendship, intimate enough to discuss the state of their marriages, far exceeding what appeared to outsiders as a mutual admiration society.

Much later, it became generally accepted he had joined the English establishment becoming a country squire after buying a fine rural estate with a fine 17th century mansion called The Rodd near the Welsh border, where he and his third wife Mary (the divorced sister of Arthur Boyd) would spend the rest of their days in almost Elizabethan splendour. And neither did much to dispel the image, making the story of the Australian-Irish lad from working-class Melbourne who became his nation’s most famous painter, member of Britain’s art establishment and eventually a gentleman farmer in the English shires with some of the highest honours the Queen of Australia could bestow, sound like fiction – if not fantasy.

I described his character recently in the introduction to “Sidney Nolan’s Odyssey” as a complex, controversial figure with a paramount passion for painting who often adopted an engaging cross-cultural blend of Irish blarney and Australian bullshit to both create and deconstruct mythologies while plumbing the depths of his own and his nation’s psyche. This image was consolidated at either end of his axis of recognition betwixt Sydney and London, when England became the Nolans’ permanent home from where, he said, his subjects, usually rooted on the other side of the world, could be depicted in the clearest light.

It is no surprise, therefore, that the most generous attention being paid to Sidney Nolan during his centenary year is in Britain where he lived the longest and thrived. There, a rich, year-long program of significant events serve to question the muted response in Australia.

His transition was already near complete when on 22 April 1987 former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, with a characteristically colourful speech, launched my original Nolan biography “Such is Life” at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The subject of the book was unable to be present, but sent a short telegram to be read out explaining he was in Dublin, where the corner of a famous hotel bar in the Irish capital was being named after him.

Nolan’s proclivity for things Irish was often regarded at worst as pretence – and a touch of the blarney at best. This overlooks his innate generosity in donating a large number of works as a foundation collection for what is now IMMA, the Irish Museum of Modern Art, housed in the restored former Royal Hospital the finest 17th century building in Ireland. Over the years he donated much of his large-scale work to institutions in Australia, but this Irish gesture came from the heart in recognition of what he regarded as a proud ancestry

In almost total Nolan mode at the time, and feeling a bit like a Boswell with many dozens of hours recorded from our conversations and transcribed for use in the biography and television documentaries, I almost went into overload when commissioned by Mode magazine’s editor Loraine Brown to compile one of their popular Insider Guides. This one, however, was too good to miss because “Sir Sidney Nolan’s London” would not only include the trip, a decent fee for a freelance writer, but the opportunity to delve deeper into his geographical metamorphosis.

Our discussions took place at his splendid apartment at Whitehall Court, the exclusive Victorian residence facing the Thames in the heart of Westminster leased for 100 years in 1976 just before Cynthia committed suicide. His own favourites from a lifetime of painting hung randomly around the walls and from the south-facing balcony he and his new wife Mary could enjoy panoramic views of the South Bank in all the capital’s changing atmospheric moods from Waterloo Bridge around to the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben.

I managed to locate the mini cassettes of our recorded conversations to refresh my memory of what was said fully thirty years ago, hoping it might explain more fully Sidney’s preference for living and working Britain, to clarify the apparent anomaly of the lion’s share of his centenary events being centred there and not in the country of his birth with which he was most associated.

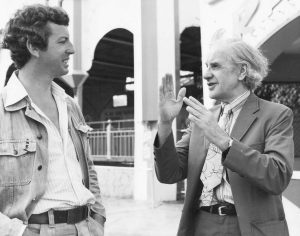

author and artist at Arthur Boyd’s studio, Bundanon, where Nolan kept a large cache of paintings, 1986.

He told me in 1987: “I have lived in London – on and off – for fully half of my life, though I cannot claim to be a Londoner. Whenever I get into a cab and ask the driver to take me somewhere, I know it’s his city and he can tell immediately from my accent that I wasn’t born here. Usually he will turn around in the driving seat, give me a quick look, and comment, ‘You don’t sound as much like a cockatoo Guv’nor as most of the people from your country’. Having made this gesture of recognition, he will expect a large tip at the end of a short journey, which I give him, knowing that most of my countrymen are not so generous. I’m always prepared to pay for my pleasures freely, and this leads to me over-tipping just to hear a cabbie’s response. It can be simply ‘Thanks Guv’ or ‘Cheers’ or ‘Have a good weekend’ but occasionally I get a sincere ‘Thank you very much Sir’ which is the height of civility and the essence of what London is all about. I sometimes take taxi rides to nowhere just to hear twenty minutes of a cabby’s conversation, which is rather like going to the theatre, except that I’m an actor too.”

In admitting that, Sidney explained a lot about his often misjudged persona. He also freely accepted he would never be a real Londoner however long he lived there (or Englishman for that matter). When he had persuaded the reluctant Sydney-based Cynthia to travel again, they arrived in Britain during 1950 for a stay of eleven months, and were based in Cambridge where Cynthia’s sister Margaret, was a doctor in general practice. They bought a car and set out on a grand tour of war-shattered Europe allowing Sidney to catch up on a whole backlog of art experiences denied him for so long. After returning for two-and-a-half productive and lucrative years in Sydney, they were back in Britain at the end of 1953 to make London their home for an unspecified duration.

“It looked just like a Georgian city,” he remembered, “exactly the scene I was conditioned to expect; the realization of all my boyhood education in Melbourne: clean, neat, ordered and imperial. I took to it immediately, feeling completely at home and decided to stay. There were some Dickensian fogs during the winter, thick peasoupers that later disappeared with smokeless fuels and clean-air campaigns, just as the polluted Thames eventually started running with fish again. In fact, I can now look out from my Whitehall apartment and see the stars shining brightly and believe this must be one of the cleanest cities in the world. And I still think it is the only manageable metropolis that allows living on a human scale.”

Those Utopian thoughts from 30 years ago sound fanciful in today’s anxiety-ridden Brexit capital bursting at the seams from a housing shortage and plagued with unacceptable levels of air pollution. Back then, however, Sir Sidney had the distinct advantage of being able to escape to his newly-acquired country estate when he needed to work in peace and be able to breathe the fresh air blowing into rural Herefordshire from the Black Hills of Wales. Things had been different during the immediate post-war years when it was imperative for creative Australians like Clive James, Arthur Boyd, Joan Sutherland, Barry Humphries, Robert Hughes and Germaine Greer to go to their natural centre of the world to satisfy career ambitions. Those who were successful stayed, Nolan among them.

“I arrived then hungry to see great art, after being deprived by the war of that essential part of a painter’s education, and devoured the works in the National Gallery and the Tate, and spent many hours in the British Museum familiarizing myself with antiquities. What was also stimulating for me, unsure of my ability to compete in this milieu, was the acceptance of my status as an artist. At that time there was the expectation that the British Commonwealth would initiate a cultural renaissance with London as its Florence, and I was welcomed as one of the participants – not specifically Australian – when rampant nationalism and chauvinistic ugliness had yet to appear. A lot of the talk was about colonials, of whatever provenance, and there was a presumption that Britain would once again adopt its rightful role in history painting, which happened to be my passion. Fortunately, I managed to slot into the scheme, with much of my work in that genre -Ned Kelly, Burke and Wills, Mrs Fraser and Gallipoli – coming from Australian subjects.”

Nolan claimed he never realized during the 1950s the influence London was having on him, while surviving on sales of his pictures in the capital and needing to return ‘home’ to Sydney occasionally to maintain buying interest from the art market there, admitting: “I assumed then that one day I would live permanently in Sydney, but I was achieving reasonable success in London and made so many friends that my world became centred there, almost subliminally.”

During the Eighties, following Cynthia’s death, Sidney and Mary would fly to Paris and back in a single day to see a couple of exhibitions and linger over a good lunch, although he was not so interested in fine food. He told me: “In London, if we want a particularly good meal we go to Wilton’s, that bastion of Britishness, for classic English cuisine, but most of the time we prefer to eat in Chinese restaurants. That must be an influence from my youth when I frequented the café’s in Melbourne’s Little Bourke Street. We’re rather fortunate living at Whitehall Court, in having the Horse Guards Hotel right next door with an excellent restaurant, although my favourite rendezvous has always been to take tea at Fortnum & Mason.”

Such civilized extravagances became the norm for a successful painter, but casting his mind back through a collage of memories within a randomly flexible timetable, he recalled how the earlier expectations of a British Commonwealth art renaissance faded after the early Sixties in the wake of American abstract impressionism, when the names of Pollock, Rothko and de Kooning were on everyone’s lips. “London, being a consumer of culture in all its forms, was only following a long tradition of accepting trends because it had always been receptive to new ideas, including those of Marx, Pollock, Mozart and Haydn. That was why I lingered there in the early days.”

Another early inducement to stay was the sense of history suggested by the Thames. “From 1960 we lived in the suburb of Putney in the south-west of the city, in a house which bordered a broad reach of the river. My studio was upstairs and I became an ardent river-watcher, noting the ever-changing life and moods, with swans gliding on the surface, pleasure boats passing at nights with lights blazing to throw abstract reflections on the ruffled water, with jazz bands playing and couples dancing, while the occasional police boat scurried by on patrol.”

Once settled into a stimulating atmosphere at Putney, the artist’s days were divided by work throughout the morning and evening, and in between he would sometimes take a bus or the Underground, to lose himself in the streets of central London. “I explored the financial district known as the City, lunched at wine bars or pubs and then wandered around looking for Wren and Hawksmoor churches. I’ve always regarded architecture as playing an important part in everyone’s life, and, in spite of the destruction wreaked by decay, fire and warfare, there was much remaining to give me an essential link with the past.”

The first inklings that this metropolis was going to be his permanent home came during those afternoon walks of discovery. “As well as looking at buildings, I’d listen to the conversations of stockbrokers and Cockney workers in the pubs and knew this had to become the navel of my world. Sydney, as beautiful as it always appeared to me in the past and subsequent visits was destined to remain on the distant perimeter and my birthplace of Melbourne was off the map altogether, except to visit my aging mother.”

Life changed for the Nolans after buying The Rodd estate: “I spend my time in England living in the country as well as the Westminster apartment and I seem to have been drawn ever closer to the British Establishment with the award of the Order of Merit, which I suppose makes me a kind of official painter or somehow the representative of the Queen as an artist. My work, I suppose, has become filtered by the softer light, although English subjects have never been part of my repertoire and I’m rather frightened of losing an Australian pitch, which, apparently I am still able to evoke.”

There were other contradictions for the artist, whose odyssey, unlike Odysseus’s ten-year struggle to return home after the Trojan War, accepted a different kind of Ithaka little by little, as if by osmosis. But along the way, this painter’s progress had fulfilled most of the advice offered by C P Cavafy in his immortal poem that one’s journey should be savoured and long, full of adventure and discovery, with rare excitements to stir both body and spirit.

Demonstrating his affinity with Britain and its capital, Nolan became a member of two leading clubs – the Athenaeum and the Garrick. The former a haven for gentleman housed in Decimus Burton’s striking Neoclassic building on Pall Mall, and the Garrick situated in Theatreland, and meant for distinguished men of the arts. He was quick to add, however, “I don’t use them very much because it’s not part of my makeup to be a clubman, even if I do admire a system that contributes to making London the most urbane of cities.”

He hastened to point out that the same quality permeated the other end of the social scale as well: “I was out buying grapes early one fine morning from a barrowman near Trafalgar Square and as he placed the fruit into a paper bag he looked up to the sky, saw dark clouds approaching and remarked ‘Some bad weather coming in from the west, Guv’.” I replied “In that case you’d better get yourself into a warm pub as soon as possible.” “Don’t worry Guv’nor,” he said, handing me the grapes and my change, “I’ll be there by half-past ten.” What a healthy attitude that was, I thought to myself, and just as civilized as lunching at the Athenaeum!”

Most of Nolan’s visits to London, once settled into The Rodd, were to enjoy art and music: frequent attendances at the Wigmore Hall for recitals, opera at Covent Garden and symphony concerts on the South Bank a short stroll across the river from Whitehall Court. He recalled a concert he attended in Westminster Abbey which recreated the vespers at St Mark’s in Venice during the 17th century. “It was a moving experience presented with exquisite finesse and while walking home along Whitehall with the strains of Cavalli and Monteverdi still ringing in my ears, I looked up at the statue of Sir Walter Raleigh and stopped in my tracks. We’d been this way a hundred times before, but something made me consider the career of this remarkable man and his adventures in the New World. It made me realize that I had done the reverse: coming from a different new world to the centre – to London.”

The artist’s regular haunts remained close to his London apartment and mostly around Piccadilly, and included Hatchards, London’s oldest bookshop founded in the late 18th century, the antique shops selling fine pieces in the Burlington Arcade, and exhibitions at the Royal Academy. “When I was leaving there the other day, I passed a shop which sells exclusive riding clothes. A black limousine was parked outside and a helmeted guard with sword drawn stood in front of the door; obviously a member of the royal family was inside to warrant the incongruous sight. It is curiously comforting to live in a place where people can do their own thing, including princes – and painters. It set me thinking that the Queen has made an enormous effort to make the Commonwealth a coherent body, devoting her life to this objective. That, of course, involves history because the story of all colonial peoples is based on control by a central power, and that fascinates me because I’ve become very interested in the organizing principles behind societies.”

Nolan said he was on the receiving end of this process as a boy in Australia. “When I began to read Shakespeare, I came to the conclusion that the same themes fascinated him because they appear as plots in many of his plays. That emphasizes for me the almost schizophrenic balance I maintain in Britain, and particularly when looking out from my London balcony to where the great dramatist’s Globe Theatre was sited. I have to wonder if, unlike him, I am approaching the subject too late in life. But in the early morning, watching the Thames reflecting the thin lines of cloud stretched across a pellucid sky, reminiscent at times of the colours I have seen on countless occasions in the Australian desert, my wish is being able to paint like Shakespeare wrote. At least we have a couple of things in common: sharing the same birthday – give or take a day or two because precise birth records have not survived – and both of us chose London to be our professional base.”

He died aged 75 at Whitehall Court in 1992 – a quarter century ago – and was buried in London’s celebrity cemetery at Highgate among 18 other Royal Academicians including Henry Moore and Patrick Caulfield. That ultimate honour for a painter came to him very late in life only the year before. In 2012, Edward Kelly and Sidney Nolan OM AC KB RA returned, in a manner of speaking, to their spiritual roots when the Irish Museum of Modern Art displayed the Ned Kelly series on loan from the Australian National Gallery and both men received a rousing reception.

Mary joined her husband at leafy Highgate after she died in 2016, and the charitable trust based at The Rodd, where she had continued to live when widowed, was left to carry out on with its stated mission as ‘an international centre of artistic practice, research and engagement inspired by its founder’s talent, innovation and passion for intellectual and cultural exchange’. But by then the name of Sidney Nolan, once one of the best-known artists in Britain had lost much of its lustre, with the Guardian newspaper stating: “Mention his name in the UK today and there might be a vague flicker of recognition. But more than likely a shrug of the shoulders.” The director of the Sidney Nolan Trust, Anthony Plant, comments “We are trying to put him back where we feel that he belongs.”

That sounds like a real challenge in the constant hurly-burly of the British art scene, but with support from the lottery-funded Arts Council England and a comprehensive program of enticing events arranged by the Trust to mark their founder’s centenary, the resolve is strong and the gamble looks odds-on to succeed for the benefit of all. On both sides of the world.

CONTRIBUTOR

BRIAN ADAMS has a long and distinguished career in the arts, as a writer and television producer/director. In charge of Arts programming at the ABC for more than 20 years, he was awarded the Order of Australia medal (OAM) for his contribution to the arts and entertainment. Creator of the “Live from the Sydney Opera House” simulcasts, his documentary portraits of several renowned Australians also became best-selling published biographies including opera diva Dame Joan Sutherland, painters Sir Sidney Nolan and Sir William Dobell, and historic figures like the botanist on Captain Cook’s first voyage of discovery Sir Joseph Banks.

Publishing history

La Stupenda: biography of Dame Joan Sutherland. (Victorian Writers’ Society prize 1980, non-fiction)

Australian Cinema: the first eighty years.

Portrait of an Artist: biography of Sir William Dobell.

The Flowering of the Pacific: Botanist Joseph Banks on Captain Cook’s first voyage of discovery.

Such is Life: biography of Sir Sidney Nolan.

Sidney Nolan’s Odyssey: a life.

A Pain in the Arts! Culture without cringe in Australia.

Ganna: Diva of Lotusland: biography of Ganna Walska, creator of Lotusland, Santa Barbara, California.

Transported! Day-by-day to Botany Bay: a journal of Australia’s First Fleet

He is currently writing The Trust – a show-business history of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust

One Comment

Join the conversation and post a comment.

Great article Brian / David – insights into the man beyond the norm – thanks to you both