It is almost 31 years since Sidney Nolan, perhaps Australia’s best known artist, died in his Whitehall Court apartment overlooking the River Thames. He had lived in England for more than 40 years, albeit with much travelling and many extended visits back to this country of his birth.

While best known for his Ned Kelly paintings, he is little known for his many paintings, writings, photographs and feelings regarding our First Nations people.

Aware of this, and saddened on the morning following the failure of the recent Australian referendum to enshrine Constitutional recognition of our Indigenous predecessors and establish a non-binding Voice to Parliament, I looked through my sundry image groupings of Nolan’s work.

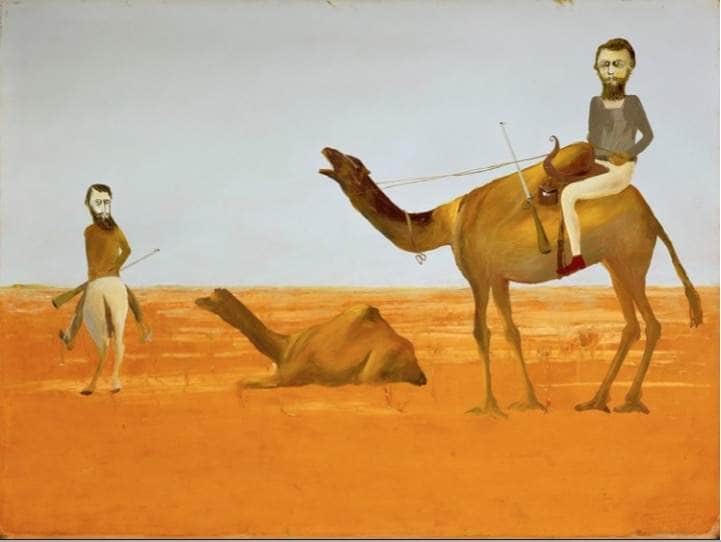

I was particularly struck by this 1962 painting “Burke and Wills expedition”, one of four I’d grouped on this theme.

The earliest of the four works is from 1948. Here we see the explorers Burke and Wills, and save for the camels, they look less like explorers than troopers on the hunt for Ned Kelly.

Sidney Nolan, “Burke and Wills Expedition” 1948, collection ACTMaG

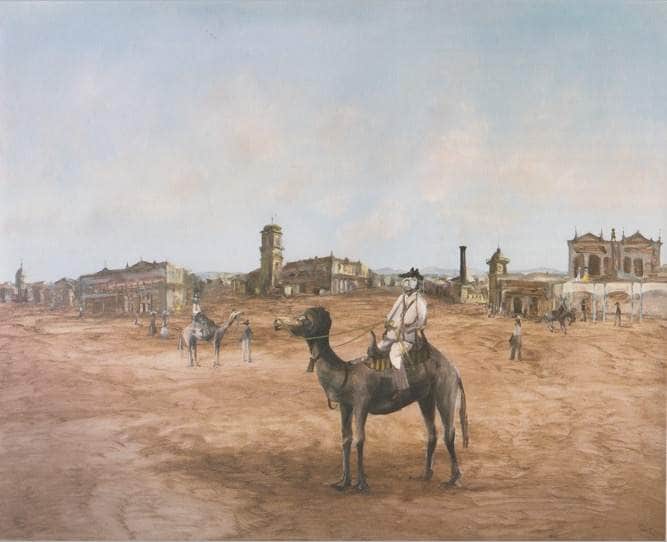

The next image was painted in 1950. “Burke and Wills leaving Melbourne” portrays their departure and shows them peering from civilisation out to where Nolan has positioned us, the viewers, on the edge of the vast unknown.

Sidney Nolan, “Burke and Wills leaving Melbourne”, 1950, private collection

Ten years later in 1961, “Burke and Wills at the Gulf” has the explorers naked and vulnerable under a brooding, menacing sky.

Sidney Nolan, “Burke and Wills at the Gulf”, 1961, collection NGV

The first of the images above is shown again below. “Burke and Wills expedition” from 1962 is chronologically the last of this grouping. Here Nolan has painted a naked aboriginal man with outstretched arm showing Burke the way …. to settlement perhaps, or to water …. to some type of salvation. Burke too is naked, but seems to ignore direction from this original custodian of the land where the expedition explores – rather, he averts his gaze and stares out towards us.

Are we perhaps Burke’s fellow travellers in this unknown? Could the painter be telling us something here?

Sixty years on I suspect he might have been, and so I wonder what Nolan’s answer would have been to our recent referendum question.

When living for several years in the 1940s with John and Sunday Reed at their artist enclave Heide on the outskirts of Melbourne, Nolan was known by the nickname “No.” This explains the title of this post, which will examine whether No would have been Yes.

In 1949 Nolan first visited the Australian outback. He flew to Adelaide, travelled by train on the Ghan to Alice Springs and criss-crossed the territory by road and light plane for two months. The view of this ancient land from above was a revelation for him and in a series of revolutionary works he painted the Australian landscape in a way no white person had before. Here are two of these paintings.

Moreover he came to not only see, but to feel for the land in a way few white people had. Thirty years after that first visit he spoke of the effect the landscape had on him.

“The implacable, beautiful landscape … How can one put it? It’s God’s gift to the world. In Australia there’s a wonderful light that shines upon it and makes it ethereal, but also makes it impossible … a wasteland.”1

“I wanted to deal ironically with the cliché of the “dead heart” … I wanted to paint the great purity and implacability of the landscape. I wanted a visual form of the ‘otherness’ – of the thing not seen.”2

However the earliest Nolan work I know having a predominant focus on the plight of aboriginal people is a 1947 painting starkly entitled “Aboriginal hunt” which shows he was alert to an aboriginal perspective of colonisation before he visited the Outback.

Sidney Nolan, “Aboriginal hunt”, 1947, private collection

We see a group of mounted men above a cliff top, and an aboriginal youth falling, almost floating down. It has been said that the scene relates to an incident in Tasmania, but I suspect it might well be based on an 1860s incident at a location known as The Leap, just north of Mackay in Queensland.

Mount Mandarana rises more than 300 meters above cliffs barely a kilometre from the main Northern highway and rail line. Known to the locals as The Gin’s Leap or simply The Leap, I travelled past it countless times during the 1950s and 1960s.

Local legend tells how in 1867, police and settlers mounted a reprisal against Aboriginal people who had been spearing cattle and stealing farm implements. Quoting directly from a 1970s account “The Aborigines fled, with the exception of a woman, Kowaha, of the Lindeman Island tribe. She was cornered with her baby in her arms and rather than surrender she hurled herself and her baby over the cliff. Kowaha died on the rocks below but, miraculously, the baby became ensnared in the brushes during the fall and survived.”3

Nolan may well have known of this incident because after leaving Heide in 1947, the year of the painting, it was in Queensland Nolan travelled for several months.4

A later work seen below is from the late 1980s. Also called “Aboriginal Hunt”, it too is said to relate to Tasmania.

Sidney Nolan, “Aboriginal hunt”, 1988, private collection

In 1951 Nolan was commissioned by the Brisbane Courier Mail to produce a series of paintings that would depict the extreme drought raging across inland Australia, and he again visited the Outback.

From these two outback visits came a series of remarkable camera images – a photographic evocation of a colonial Sublime, one like no other. These photos, even with people and animal carcasses centermost, display a backdrop best characterised by the single word ‘dread’. They included photographs of a first people whom Nolan realised had very much become second.

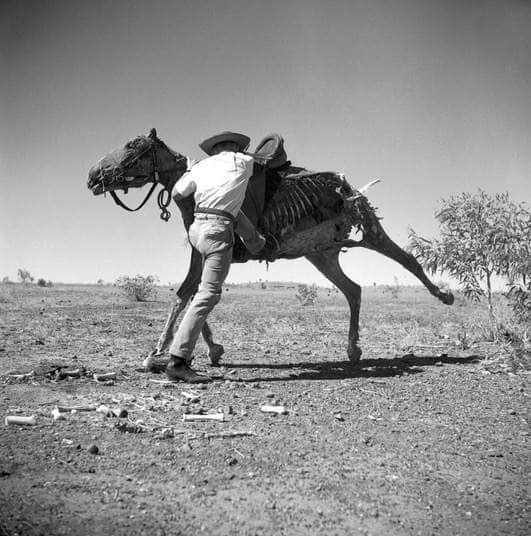

His photograph below of Brian the Stockman at Wave Hill Station Mounting a Dead Horse was chosen by Damian Smith, a contributor to The Nolan 100 – a 2017 Centenary tribute. He said this: “Of all of Nolan’s vast outpouring, this photograph remains, in my mind, a work of originality, inventiveness, forward thinking and compositional panache. It is as artworks should be, utterly of its time and utterly timeless.”5

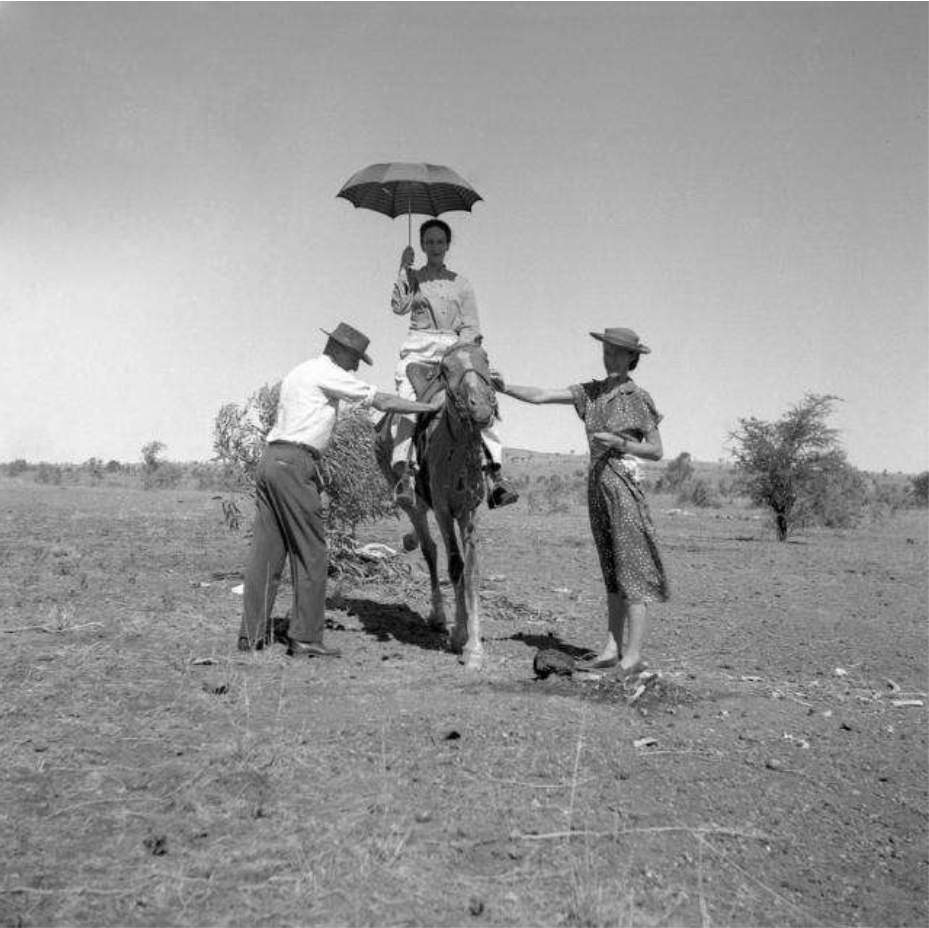

Below we see Nolan’s camera eye at its best. Brian the Stockman’s skeletal steed is mounted by a parasoled Cynthia Nolan, the whole assemblage propped up by no less than the manager of Wave Hill cattle station assisted by his good lady wife. Are there better images than these to parody the sentiment espoused by some supporters of the No campaign in the recent referendum, of colonialism working for the betterment of all?

That drought had been long and hard. It laid waste to the inland, parched the soil, withered the vegetation. Horses and cattle alike died of thirst. Their carcasses lay bleached and desiccated under the sun.

Scroll through the following images and consider just what these carcasses speak of.

From these photos, Nolan painted a series of works that became known as the Carcass paintings. Here are two of them:

In 2017, Nolan’s centenary year, a number of exhibitions of Nolan’s work were staged around the world. The catalogue for the exhibition at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, UK has an essay by Dr Kate McMillan, “Sidney Nolan and the Colonial Sublime”, which bears on these themes.6

McMillan contends that an Australian art of landscape has effectively been complicit in “the absorption of certain histories at the exclusion of others.”

If, as I contend, history is seen as a chronicle of dispossession, then the so-called history wars surely centre on this selective absorption of one history rather than another.

“Only history-telling conducted in the margins,” she writes, “has voiced the violent, state-sanctioned genocide of over 350 language groups across the continent.”

“…. despite hundreds of massacres recorded – the last one in 1928 – not one photograph or painting exists of them. The absence is terrifying. The imaging of Australian history has been so partial, and in many instances simply false, that it is only ever possible to view Australian landscape as anecdotal, part of a broader nation-building project closely aligned to propaganda.”

Turning to the drought photographs and paintings Nolan made in 1952 and 1953, she sees in their haunted images not just pastoral relics of a devastatingly bad drought, but a visible record of a “place unsettled and unsettling”, a badland.

She says that Nolan’s images “record the presence of a bad spirit”; indeed they portray “the rotting carcass of colonialism in miniature” and “speak back to a nation about itself, and to Britain of its colonial legacy.”

McMillan stops short of seeing the withered horse and cattle carcasses as a substitute, a metaphor perhaps, for the countless massacred Aboriginal bodies not left beneath the withering sun to desiccate, but burned to remove evidence of their slaughter. Once having made that connection though, who will ever again be able to look on these images of Nolan’s with the same eyes?

In my view, the drawing of such conclusions from these works would not have been unintended by Nolan, who was said by close associates to do nothing unintentionally.

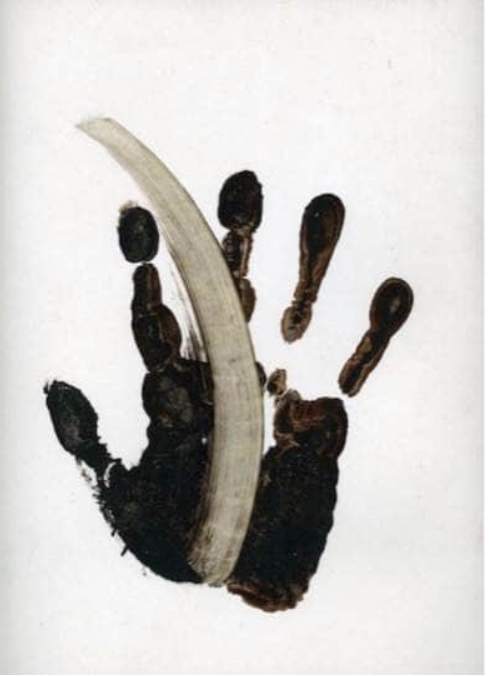

Back in 1981, Nolan designed the sets for the Covent Garden production of the Saint-Saëns opera Samson and Delilah which was directed by the young Australian Elijah Moshinsky, who later recalled how Nolan created this image.

“The effect in performance would be that we saw the Israelites obscurely in white and blue sections of the stage picture, and the imprint of the black hand would act as a void through which we could see the disposed Hebrews clearly.”

“This symbol, he explained to me, came to him from aboriginal rock paintings. It was, he said, the first expression of Man’s self awareness. For Nolan, it was a symbol of creativity in man, The Hand of God.”7

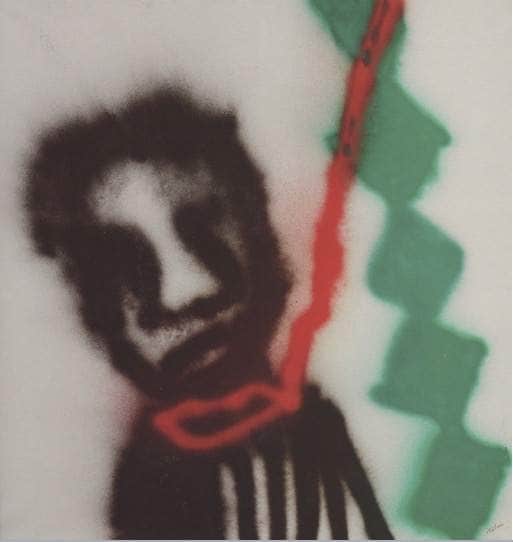

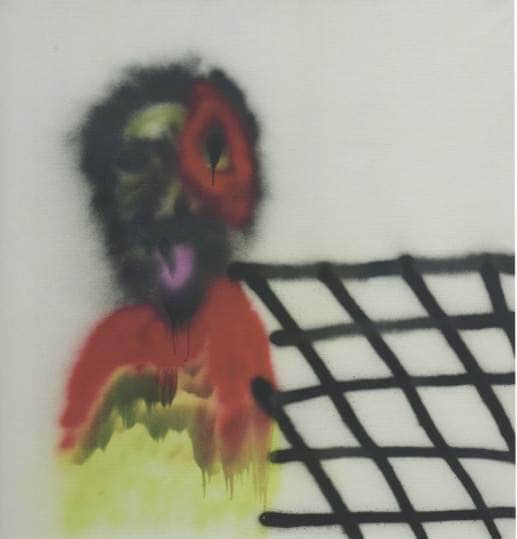

Then in the late 1980s Nolan worked on a series of huge spray paintings on the theme of Aboriginal deaths in custody. In his Centenary year, these paintings were exhibited at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham.8

The image below is one of the most striking in that series.

And here are two more:

Although Nolan said he’d rather paint what he had to say rather than say it, his words – eloquent and spoken with passion – testify to the plight of First Nations people as effectively as do his paintings.

“… the Aborigines actually had a fantastic culture. A very very beautiful people and a wonderful synthesis of another world and this world. … it is one of the most fantastic cultures that ever existed, including the Egyptians and everything else. It’s gone on for 40,000 years.”9

The following year Nolan used words which would not have been out of place in Paul Keating’s 1992 Redfern speech delivered just 12 days after Nolan died. Keating spoke of “Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life.”

Four years earlier Nolan had said …

“The Aborigines epitomise what Europe went through with the concentration camps, and everything else. We imported our particular ethos and applied it to that landscape, or moonscape, or whatever you are going to call it. We deprived both the landscape and the people who are in it – who have been in it for 40,000 years and have learned to love it, to adore it, and to worship it. It was their sustenance and their survival, and they made a myth out of their survival. They used to talk at night about, ‘how we survived this day’. Well, we actually ruined all that.”10

and this …

“It’s what I have to do when I go out to the Kimberleys now: I have to look at it and say, ‘This is where a great civilisation became doomed’.”11

Approaching the age of sixty and looking ahead, in 1975 Nolan asserted “What an artist really wants is to say something which, one day, out of contemporary contexts, will mean something important, will be sure of survival.”12 I am confident that his statements referenced here – both those written and those painted – will mean something important, and will be sure of survival.

So … returning to the question posed in the title of this post – how would Nolan have voted in the recent referendum?

I have little doubt.

NO would surely have been YES.

It is interesting to contemplate whether No would also have been Yes in Australia’s previous referendum in 1999, which also failed, seeking to establish an Australian Republic. In spite of his knighthood, I rather suspect he could well have been less royalist than most would think. Let that await another post.

END NOTES

- Interview with Peter Fuller, “Sidney Nolan and the Decline of the West: A Modern Painters Interview with Sir Sidney Nolan,”Modern Painters, Vol.1, No.2 (Summer 1988); quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his Own Words (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2007), p. 344.

- Sidney Nolan, quoted in Elwyn Lynn and Sidney Nolan, Sidney Nolan – Australia, Bay Books, Sydney, 1979, p. 13.

- John Larkins, Australian Pubs, Adelaide, Rigby, 1973.

- One possible problem with this theory is that the reverse of the painting is dated 25 May 1947, two months before Nolan travelled to Queensland, although it is not inconceivable that the reverse was incorrectly dated years later. Equally, a similar incident to that of The Leap in Queensland, could well have happened in Tasmania and Nolan may have known of this – either via John Reed or Nolan’s wife Cynthia, John Reed’s sister, whose moneyed pastoralist forebears lived at Evandale near Launceston; or Nolan may have learned the story during a long cycling trip through Tasmania in 1940.

- Damian Smith, No. 20 in The Nolan 100, Brian the Stockman at Wave Hill Station Mounting a Dead Horse, http://www.sidneynolantrust.org/nolan-100/20-brian-the-stockman-at-wave-hill-mounting-a-dead-horse-damian-smith, retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Kate McMillan, “Sidney Nolan and the Colonial Sublime”, in Transferences: Sidney Nolan in Britain, ed. Rebecca Daniels, Pallant House Gallery with Sidney Nolan Trust, Chichester, 2017, p. 53.

- Elijah Moshinsky, No.15 in The Nolan 100, Study for ‘Samson et Dalila’, http://www.sidneynolantrust.org/nolan-100/15-study-for-samson-et-dalila-elijah-moshinsky, retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Jane Clark, “Every conceivable approach of eye and mind …”, catalogue essay, Sidney Nolan, Ikon Gallery and Sidney Nolan Trust, Birmingham, 2017, p. 9.

- Interview, Jancis Robinson, Thames ITV, 15 December 1987; quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his Own Words (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2007), p. 295.

- Interview with Peter Fuller, “Sidney Nolan and the Decline of the West: A Modern Painters Interview with Sir Sidney Nolan,” op. cit., p. 344.

- ibid, p. 349.

- Charles Osborne, Masterpieces of Nolan, London, Thames and Hudson, 1975; quoted by Lyrica Taylor, STILL SMALL VOICE: British Biblical Art in a Secular Age (1850-2014), from the Ahmanson Collection, The Wilson (Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum), Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, 2015.

One Comment

Join the conversation and post a comment.

I .like it. Much food for thought here.