This essay by Felicity Moore pairs nicely with Simon Pierse’s Another look at Nolan in examining and paying tribute to Nolan’s art-making and universality – this piece examining the pivotal role of First Class Marksman, the other seeking an emotional source and intensity. Both take a wry look at the awry in Nolan. Here, Felicity St John Moore draws together her studies on the role of Danila Vassilieff in Nolan’s first series Kelly paintings in light of some new research regarding First Class Marksman and its Janus-faced Ned Kelly.

A TRIBUTE BY FELICITY ST JOHN MOORE

Challenged in Excited Reverie: Sid, Ned and Dan

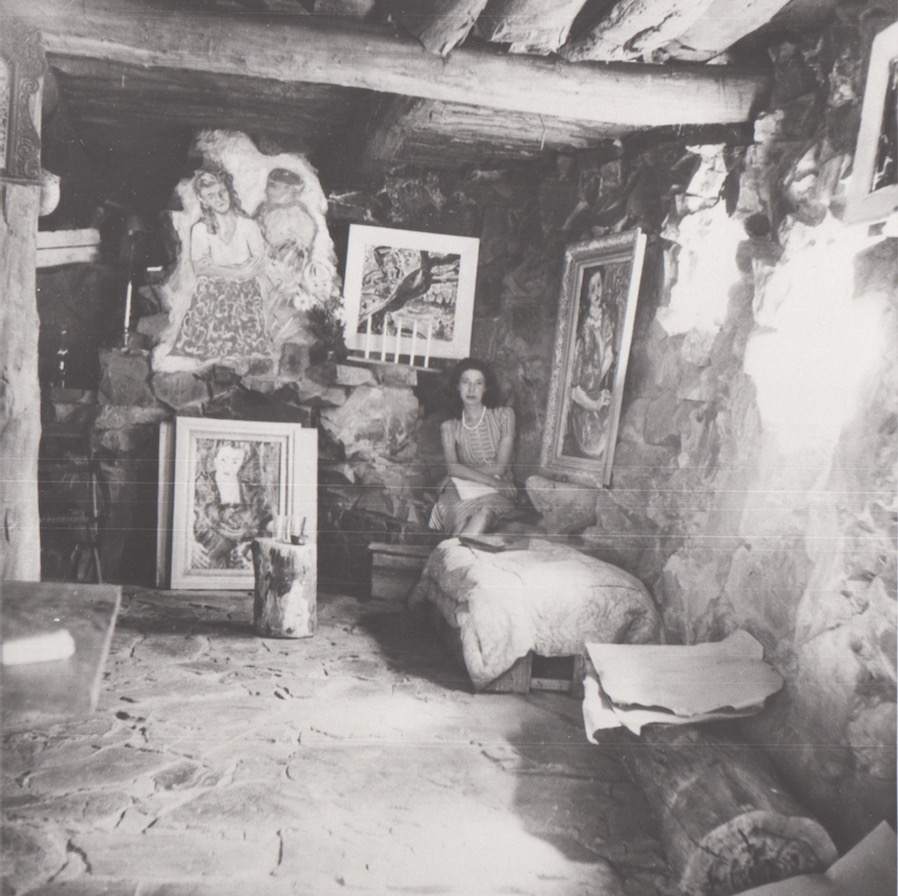

First Class Marksman is an exceptional painting in the Ned Kelly series for two reasons. The first is that it was not executed at Heide (and thus not in collaboration with Sunday Reed) but at the older artist Danila Vassilieff’s house Stonygrad that Danila had built into and out of the rocky hillside at Warrandyte.

There Marksman would have been created in Vassilieff’s stone-floored bedroom studio, whose log-lined roof was held up by a single tree pole.

Over the hearth was a fresco of Danila and his mistress (her husband interned) that he boasted ‘would last forever like the Sistine Chapel’.

Original living room at Stonygrad with fresco above fireplace of Vassilieff, Lotte Schumacher and her children. Photograph: Edward Cranstone

This earthy space was lit by candles, a hanging kerosene lantern and half-moon windows at ground level.

Nolan told me that Vassilieff was the most spontaneous person he had ever met. By way of contrast, Nolan’s own sojourn at Stonygrad which he told me he had offered to caretake in the later months of 1946, was carefully plotted and planned.

The second reason is that the title does not relate to a particular incident in the Kelly legend. The title is instead ironic as the ‘haptic’ finger-painted digits on the trigger suggest. Nolan provided this ambiguous title, First Class Marksman in 1948 (after he had left Heide for good) to meet John Reed ‘s request for the same for the first exhibition of the Ned Kelly series. But Nolan’s chosen title doubled as a reference to Vassilieff the man, the precision of whose hand and eye was legendary.1

With a gap between ‘marks’ and ‘man’, it referred also, and especially, to Vassilieff the teacher whose individual marking system as the art teacher at Koornong Progressive School was embedded in his personal myth. This system consisted of improving the children’s marks each term regardless (sometimes to 120 % or more) in order to boost their confidence .

This double or triple entendre title is the clue to decoding the broader meanings of First Class Marksman: and to the casting of Ned Kelly from a provincial legend to a European ‘anti-hero’ level. Stonygrad was the place where Nolan created his own personal myth, and the place where he forged his connection to the real. First Class Marksman embraces Danila’s belief in ‘creation not destruction’ and his knowledge that everything came from the same source in nature – the self. The memory of Vassilieff’s house infiltrated Sid’s personal myth and his future Kelly paintings all make some reference to this source.

Sidney Nolan, “Burning at Glenrowan” and “Siege at Glenrowan”, October-November 1946, collection NGA.

For example, the single tree pole that holds up Danila’s roof is the connecting image for the Glenrowan paintings; the suspended lantern that lights his studio unites Nolan’s three Kelly Interiors; and the half-moon windows that top the windows in The Trial echo those on ground level at Stonygrad.

In certain respects, First Class Marksman can be understood as Nolan’s answer to Vassilieff’s criticism of his imagery for its lack of depth because it was from the head not the gut. This would suggest that Nolan intended First Class Marksman to impress Danila on his return (he sent a note and came back earlier than expected), and hopefully as a handshake to the Slav soul, in line with the ‘Never to be sold’ inscription on the back and the cocked finger on the barrel .

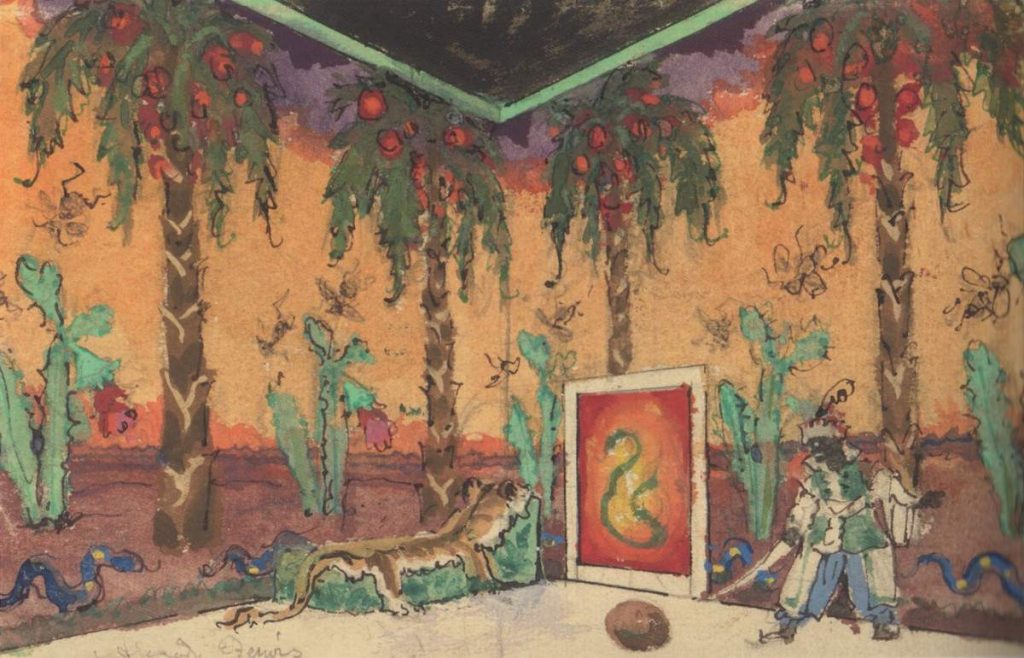

My essay “Vassilieff to Nolan” in The Ballets Russes in Australia and Beyond, ed. Mark Carroll)2 explores connections between Nolan and Vassilieff resulting from Nolan’s caretaking of Stonygrad towards the end of 1946, and particularly the four panel screen Expulsion from Paradise created by Vassilieff in 1940. Commissioned by Warrandyte art lover Connie Smith, it was rejected by Connie’s husband because of its pointed innuendo. Returned to Vassilieff, it was kept in his studio at Stonygrad where Nolan would have seen it.

It took me years to discover that Vassilieff’s Expulsion from Paradise screen was actually a hybrid of the biblical story and the folk legend of Petrouchka, the latter related to the Ballets Russes scene cloth, by Alexandre Benois, for the Moor’s Room.

This discovery, entailing a scrutiny of both sides of the screen, became the basis for an astonishing revelation: in short, that the paintings and sketches on the back of the Expulsion screen were in the manner of a ‘modern’ iconostasis – laden with surprise and humour, and related to the members of the Ballets Russes and its productions.

In turn, this belated discovery of the Ballets Russes iconostasis answered the challenge that Nolan had set me in 1980 – to find the trigger of his Kelly paintings.3 That conversation came out of our meeting at the official Lanyon Gallery reception for his major gift of Kelly paintings. In our telephone interview that same evening I realised that Sid’s experience at Stonygrad had affected him profoundly, that it was indeed epiphanic. He informed me that his stay at Stonygrad could be dated by First Class Marksman for the Kelly series. This single painting was painted in Vassilieff’s wonderful house and it was pivotal to the Kelly series. He then described Danila as being pivotal to First Class Marksman, and in turn as the trigger of his art. When I asked him to tell me more about this trigger he closed up, instead issuing me with a challenge. “No I’m not going to tell you” he declared, “but it’s up to you to find out.”

But the relevant image of the ‘blackamoor’ from Petrouchka, which triggered Nolan’s ‘blackamoor/ black armour/ black amour’ wordplay connection, was located on the back of the missing Expulsion from Paradise screen. And that seminal screen lived in a private collection in Warrandyte, its discovery prevented by Danila’s estranged and vindictive widow.

Even after its lucky rescue by the National Gallery of Australia in 1983 (in advance of a devastating bushfire) the vengeful figure of the pointing blackamoor in the background of Party scene was not detected. Nor was it spotted by me until an official replica of the Paradise screen was made for the Journey to Mildura exhibition with the iconostasis scenes upended for public display.

Only then, and who knows how, did the ‘devilish’ blackamoor emerge in the outside space on the right of the period dresser in the centre, pointing and/or pissing at the disguised figure of Adrian Lawlor (Connie’s secret lover, Danila’s temporary enemy and Nolan’s ‘bete noir’). This pointing gesture links the two devils – the black devil and the ‘green devil’ (of Lawlor in green frog-suit costume and beard) – joining types from two different sources and spaces, the universal to the particular, the magical folkloric world of ballet to the real provincial .4 According to Michael Keon, Lawlor and Nolan had different sensibilities; they disagreed and argued.5

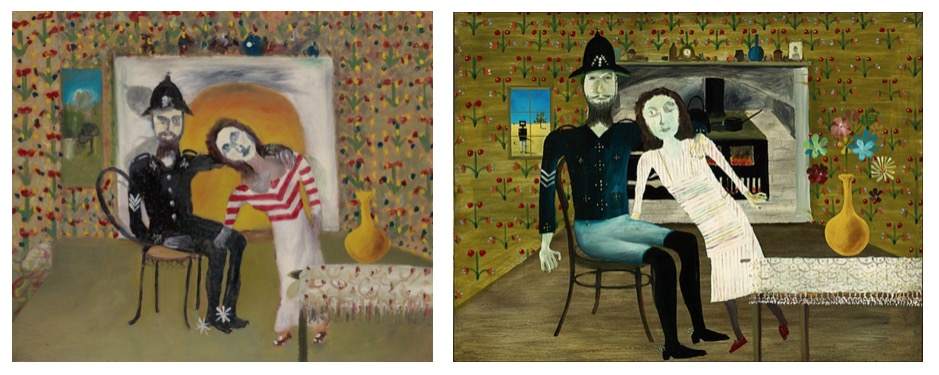

Left: Sidney Nolan, study for “Constable Fitzpatrick and Kate Kelly”, 1945-6, collection NGV; Right: “Constable Fitzpatrick and Kate Kelly”, October 1946, collection NGA.

In Nolan’s humorous and telling reworking of Vassilieff’s Party scene into his Kelly seduction episode , namely Constable Fitzpatrick and Kate Kelly, he continues the game; changing the couples, his alter ego with Lawlor as the lecherous policemen black amour (reflecting the duality of his own life) and Connie into Sunday Reed; while the avenging figure of Kelly (visible through the window) is the ‘third party’ pointing black armour in the ménage a trois message. This connecting trigger was a touchstone to his Sunday symbol on the right that tells of his epiphany through the festive altar cloth, used during Epiphany, and a luminous flask with flowers in its throat. Through the symbolist iconic aesthetic carried by Vassilieff, Sid’s narrative links back to Russian modern art, the Diaghileff aesthetic and the reciprocity of Matisse.

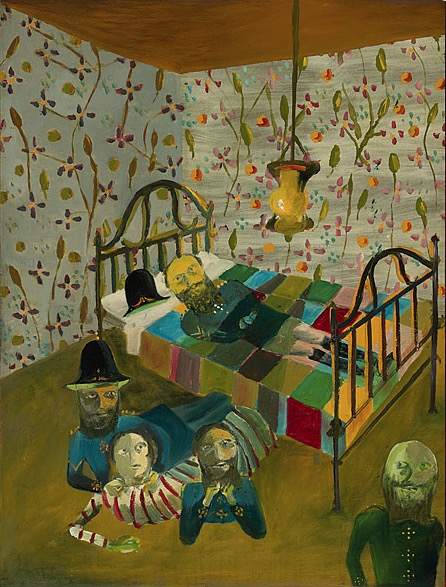

There followed Nolan’s second interior episode: his Stonygrad studies for The Defence of Aaron Sherritt, in which the prone figure of the trouser-less police officer doubles as his thinking ‘caretaker’ alter ego, helmet at the ready, stretched out on the half real check quilt of Danila’s bed (with added colours and lively fence ends). This cogitating alter ego figure lies under Danila’s kerosene lantern and a fresh floral mural,6 and over the under-the-counter’ extras/characters who crawl out of the unconscious depths below.7 This jostling of messages is assisted by references to child psychology and a naive aesthetic that adds a new depth of meaning to his final version of The Defence of Aaron Sherritt.

Nolan was going for his life, hot on the heels of his earlier Kelly paintings, as in The Chase where he clearly identifies with the heroic policeman, at full gallop as he heads towards the horizon while also rounding on his quixotic striped target – the chestnut-mounted warrior, tilting at the sky with his gun, its trigger eye on Venus.

During our telephone interview, Nolan had described Vassilieff as a ‘natural’ who tended to speak in metaphors. The simplicity of his words gave them a greater impact he said, for instance his insistence on ‘the message not the aesthetic’. But Nolan thought it impossible for a painter to avoid the aesthetic. Danila may have believed what he said and it was true in a sense because he possessed an inborn aesthetic which allowed him to have it both ways. This question was the setting for Nolan’s loosening the straightjacket of modern aesthetics and including more possible internal narratives and a wider range of styles.

Before Vassilieff, Nolan’s own sources were predominantly theoretical, he “was picking up on a theoretical base as a painter”, as he often said. There is a world of aesthetic difference between Constable Fitzpatrick and Kate Kelly (in which the collage-style figures resemble cut-out puppet dolls) and the multi-level, iconic, episodic variants that follow.

In Quilting the Armour, for instance, the black armour lies in the foreground as a foreboding of future events, a second coming or Mary at the tomb of Christ; while the farm cottage in the background takes the armour made of plough shares back to its original source in the Victorian countryside. These allusions open the narrative to time and place. They tackle the theme of depth and of layered messages/ meanings directly. Thus the ‘star-struck’ figure of Kelly’s sister, Margaret pointing her needle/trigger into the lining of the empty headpiece has deeper meanings. Her needle is part of the narrative of the naturalistic landscape. But her loving action also touches back to the Venus myth, and the suit of armour to Mars, with the red robin on the fence reminding of Nolan’s escape from the military police.

The coupling of love and war, of legend and myth with the real narrative is again the subject of Marriage of Aaron Sherritt.

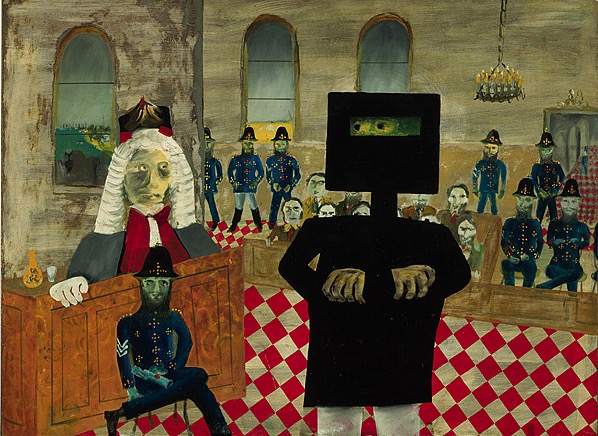

In The Trial, his third Stonygrad-related interior, the conflicting aesthetic styles looks as if they too are on trial. European perspective is being manipulated as the surreal armour of Kelly towers over the courtroom floor, backed by the unresolved cluster of deadpan jurors; the real Streeton style impressionism through the windows vies with the red and white harlequin floors; the ‘mock reality’ of the Judge’s bench questions the judgement, carrying its own message; the placement of the bearded officer below, double jointed and holding the death sentence is part of the plot, and so on. Nothing is left to chance. Nolan piles it on as though his own future life were at stake in a courtroom lit by real half-moon windows and Danila’s hanging lamp.

Compared to these paintings, First Class Marksman stands out as a kind of hymn to creation not destruction, which was Danila’s stated goal when he arrived in Australia. Nolan celebrates himself at once as the source and secret subject of his own creation, as making his whole mark, literally as well as metaphorically, through his aesthetic handling of colour, pigment, brushwork and imagery, including his marriage of message and aesthetic. First Class Marksman joins the mythical and the real, the Ned Kelly legend and the Australian landscape.

On a separate level, Nolan clearly intended it, along with the equivocal title, to impress the returning Vassilieff and win marks for improving his performance at Stonygrad.

In this grand composition, the iconic image of the armoured outlaw stretches upwards on the picture plane. Puppet-eyed and with black ‘pupils’ within his black square mask ( itself associated with the Russian Revolution in which Danila had fought and lost), he is Janus-faced, seeing things both ways, inside and outside, across time and space. He looks back to the 19th century landscape and forward, through his bushman presence and brushed arms, to firing his paint-handling and thinking directly into the waiting space of the contemporary Australian landscape. His mark is his message – of guts, heart or whatever, as elusive as life itself.

CONTRIBUTOR

FELICITY ST JOHN MOORE is an art historian and curator who spent several years on the curatorial staff of the National Gallery of Australia. Her publications include Vassilieff and his Art (Oxford University Press, 1982); Vassilieff and his Art, second expanded edition (Macmillan Art Publishing 2012), and catalogues for exhibitions she curated for the National Gallery of Victoria: Classical Modernism (1992), Charles Blackman: Schoolgirls and angels (1993), Sam Fullbrook (1995) and Charles Blackman: Alice in Wonderland (2006). Recent exhibitions include Danila Vassilieff: A New Art History, (Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2012, with Kendrah Morgan) and Vassilieff: Journey to Mildura, (Mildura Arts Centre, 2013). This last exhibition formed the basis of the documentary film, on which she collaborated with her son Richard Moore, Danila Vassilieff; The Wolf in Australian Art, launched with Q&A sessions at NGA, AGNSW, NGV and other galleries. She is an Honorary Fellow (Fine Arts) at the University of Melbourne.

END NOTES

- Vassilieff was reluctant to kill anything after his forced execution of officers during his imprisonment by the Red Army.

- The Ballets Russes in Australia and Beyond, ed. Mark Carroll, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2011, p. 133.

- Sidney Nolan, telephone interview with the author, Canberra, 6 March 1980.

- Lawlor was a prominent figure in the Contemporary Art Society.

- Nolan regarded the Paradise mural in the Nields’ bathroom as Danila’s best painting. It had God on the ceiling and the green Devil rising from the toilet bowl.

- Similar to the Paradise mural in the Nields’ bathroom.

- Danila’s lamp occupied my attic for years.

Recent Comments